Study findings to guide NEA in establishing an e-waste management system for Singapore

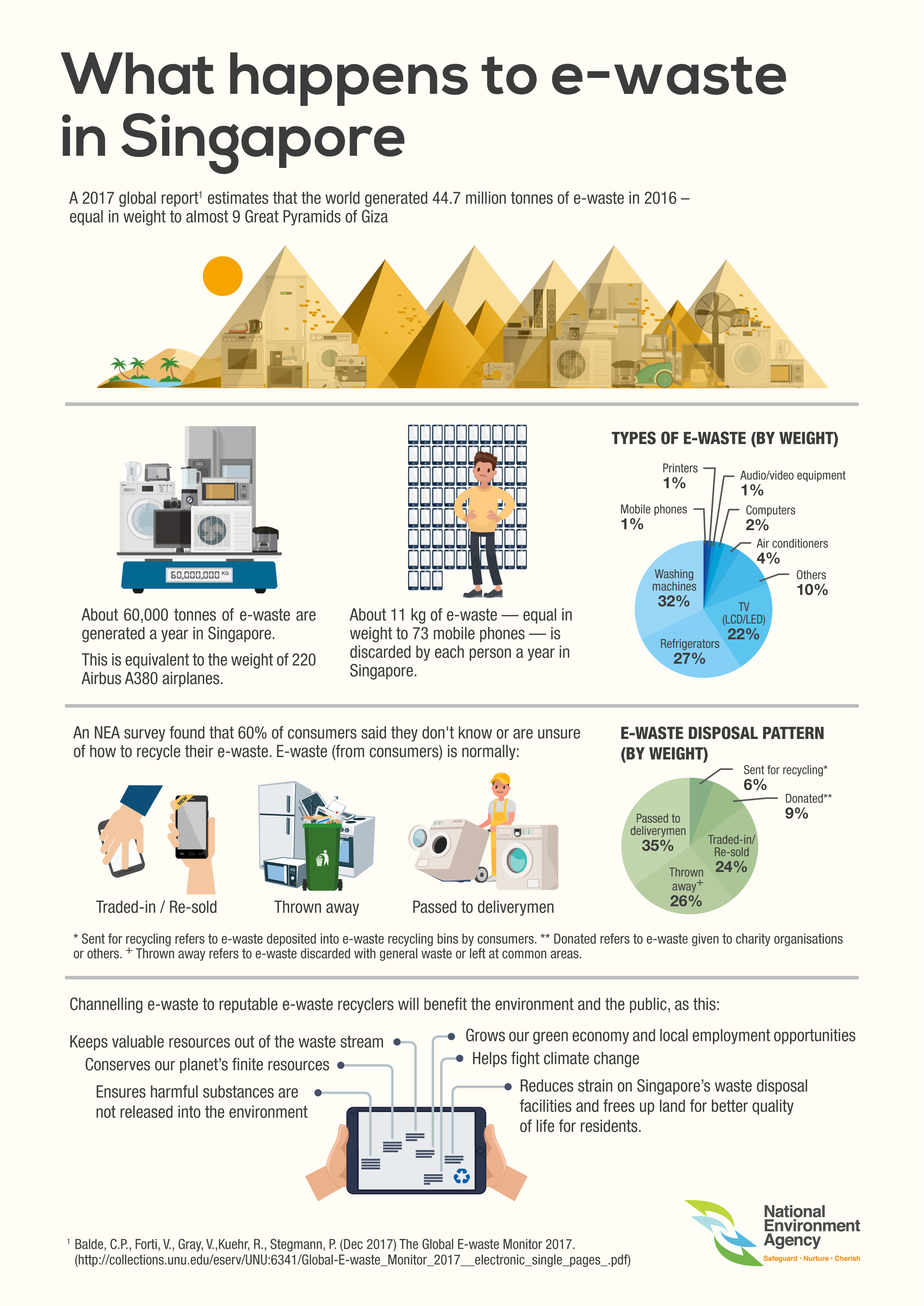

Singapore, 19 January 2018 – Each year, about 11kg of electrical and electronic waste (e-waste), equal in weight to 73 mobile phones, is disposed of per person in Singapore.[1] This amounts to more than 60,000 tonnes of e-waste generated in Singapore a year. A study commissioned by the National Environment Agency (NEA) showed that 60 per cent of Singapore residents do not know or are unsure of how to recycle their e-waste.

Key findings from NEA e-waste study

2 The study, conducted from April 2016 to October 2017, was aimed at identifying the challenges in Singapore’s management of e-waste, and developing a comprehensive system to address these challenges. The study, which looked into the e-waste disposal patterns of consumers, found that consumers typically trade in or sell e-waste of high value (e.g. mobile phones), while they discard the rest with their general waste. Bulky e-waste (e.g. washing machines and refrigerators) is mostly carted away by the deliverymen when new appliances are delivered, but is sometimes discarded improperly (e.g. left at common areas).

3 The study also found that e-waste that is discarded or carted away by deliverymen could end up with informal collectors such as scrap traders and rag-and-bone men. These collectors refurbish reusable electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) for sale, dismantle the rest and trade the parts extracted with recyclers. Many of these collectors do not have the capability to maximise resource recovery from e-waste, and as a result, only components of significant value are recycled. In Singapore, e-waste that is not recycled is incinerated, which results in the loss of resources as well as in carbon emissions, contributing to global warming and climate change.

4 In addition, the processing of e-waste by these collectors can result in workplace hazards and poor environmental practices. These include the venting of harmful refrigerants from refrigerators and air-conditioners to the environment and discarding of potentially hazardous unwanted components with general waste. Heavy metals in the e-waste incinerated also contaminate the incineration ash which is landfilled at Semakau Landfill. A regulated system is therefore needed to ensure that i) consumers are provided with convenient means to recycle their e-waste, and ii) the e-waste collected is channelled to proper recycling facilities where safety and environmental standards are adhered to. Please refer to Annex A for more details of the e-waste disposal patterns of consumers, and Annex B for more details of the e-waste landscape of Singapore.

Learning from established e-waste management systems

5 NEA has been working to raise public awareness of the need to recycle e-waste and to encourage participation in voluntary programmes where proper recycling and treatment processes are adopted. The most extensive programme is StarHub’s RENEW, in which more than 400 e-waste bins have been placed across Singapore. While this is encouraging, there are limits to just having a voluntary approach. Such programmes typically only result in the collection of portable info-communication technology (ICT) equipment, and the amount of e-waste collected is only a fraction of the total amount of e-waste generated annually.

6 In order to develop a more comprehensive e-waste management system for Singapore, the study also looked at best practices in established e-waste management systems around the world. Many countries and cities, such as Germany, New York, Japan, Sweden and South Korea, have formal systems to manage e-waste. The study found that the active participation of stakeholders is necessary to ensure that e-waste can be managed effectively and efficiently. In particular, producers (e.g. brand owners and manufacturers) play a critical role in designing products with greater potential for resource recovery.

7 In view of this, a common feature in established e-waste management systems is the assignment of responsibilities to the key stakeholders in the e-waste value chain, known as the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) approach. Under the EPR approach, producers ensure that their products are properly recycled upon reaching their end of life, by fulfilling e-waste collection targets and channelling the e-waste collected to formal recyclers. For example, in New York, electronics manufacturers fund programmes where consumers can mail small e-waste to recyclers.

8 As retailers are the touch points for consumers, many established e-waste management systems rope in retailers to provide convenient collection options for consumers. In Germany and Sweden, large retailers are required to provide e-waste collection points in their stores, as well as free one-for-one take back services for larger e-waste upon the purchase of a product.

9 The co-operation of consumers in channelling e-waste to proper collection avenues is also essential. In the places studied, governments often lead outreach and educational efforts on e-waste, with the support of other stakeholders. These efforts ensure that e-waste is channelled to formal recyclers, which typically need economies of scale to sustain their operations.

10 In the established e-waste systems studied, e-waste recyclers are also regulated to ensure that their recycling processes meet high environmental standards. Recyclers in European Union countries are subject to recycling targets, and manufacturers and recyclers are required to submit information on e-waste flows to regulatory bodies.

Next steps

11 The Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) and NEA are studying the best practices adopted by other countries, and are assessing their suitability for Singapore through stakeholder consultations with the industry. MEWR and NEA will also be seeking public views on e-waste via a consultation session in February 2018.

[1] Assuming a mobile phone weighs 0.15kg.

~~ End ~~

For more information, please contact us at 1800-CALL NEA (1800-2255 632) or submit your enquiries electronically via the Online Feedback Form or myENV mobile application.

ANNEX A

ANNEX B

Background of e-waste management in Singapore

Introduction

1 Singapore generates more than 60,000 tonnes of electrical and electronic waste (e-waste) every year[2]. The rate of e-waste generation is expected to increase in tandem with economic growth and the quickening pace of product replacement. A recent international report estimated that globally, e-waste generated per year jumped 8 per cent from 2014 to 2016. Experts cited in the report foresee a further 17 per cent increase by 2021 – making e-waste one of the fastest growing waste streams[3].

2 A significant portion of this amount can be reused and recycled if handled and dismantled properly. For example, individual components such as motherboards can be extracted from used computers for refurbishment, while other materials such as plastic and metal can be recycled. The reuse and recycling of e-waste would conserve our planet’s finite resources and cut the amount of waste going to our incineration plants and landfill. In Singapore, the problem of our growing waste generation is especially worrying. Singapore currently has only one landfill, which will run out of space by 2035. In the future, Singapore may not have enough land or sea space to build incineration plants and landfills we will need to handle our quickening pace of waste disposal.

3 In addition, e-waste contains small amounts of heavy metals. The heavy metals will end up in our incineration ash if e-waste is disposed of as general waste. By recycling e-waste, we can reduce the amount of heavy metals in our incineration ash, increasing the potential for developing future upcycling solutions for incineration ash.

4 E-waste also contains substances that can cause environmental and public health issues if not handled properly. For example, refrigerators and air-conditioning systems may contain gases that can harm the ozone-layer or contribute to global warming if released into the environment. Improper handling of e-waste could also expose workers to toxic substances such as cyanide, which is commonly used to extract precious metals from e-waste. Some e-waste, such as batteries and lamps, can also contain flammable substances.

5 A regulated system that ensures that e-waste is properly disposed of would not only ensure that as much e-waste as possible is reused or recycled, but also prevent harmful substances from impacting the environment or human health.

Upstream controls to limit impact of e-waste

6 Singapore has put in place upstream controls in the form of a framework on the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (SG-RoHS), that limits the amount of hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (EEE). The framework, adapted from the European Union (EU) RoHS Directive, restricts six hazardous substances in six controlled EE. The six EEE and their prescribed restrictions are listed below:

| 6 Restricted Hazardous Substances | Allowable Concentration Limits | Controlled EEE |

|---|

| Lead (Pb) | Maximum 1,000ppm (0.1% by weight) | Six identified EEE : mobile phones, mobile computers, refrigerators, air conditioners, panel TVs and washing machines. |

| Mercury (Hg) |

| Hexavalent Chromium (Cr VI) |

| Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBBs) |

| Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) |

| Cadmium (Cd) |

Maximum 100ppm (0.01% by weight) |

7 The upstream controls, which came into effect in June 2017, will reduce the potential of hazardous substances entering our waste streams.

Building ground-up momentum to tackle e-waste

8 To limit the impact of e-waste from the cradle-to-grave perspective, the National Environment Agency (NEA) has been working with industry partners and communities to improve the recycling of e-waste. In 2015, NEA formed the National Voluntary Partnership for E-Waste Recycling to provide support for businesses and communities interested in promoting e-waste recycling to the public.

9 The partnership consolidates the efforts of the industry and community under one umbrella, and also provides funding support for those under the partnership to expand on their public recycling programmes. To date, NEA has formed 17 partnerships with industry stakeholders. The members of the Partnership are listed below:

| Companies/ Organisations |

Producers/ Retailers |

Venue Partners |

Recycling Service Providers |

|

- HP

- Panasonic

- SingTel

- StarHub

|

- SingPost

- City Developments Limited

|

- Cimelia

- DOWA Eco-System

- ELMS Industrial

- Esun International

- HLS Electronics

- Metech Recycling

- SMC Industrial Pte Ltd

- TES

- Virogreen

- Vemac Services

|

10 There are several active voluntary recycling programmes in Singapore. In June 2017, SingTel and SingPost jointly launched ReCYCLE, an initiative that allows consumers to drop off their unwanted electronics at SingTel shops and SingPost branches, or mail them in for free. Further examples of e-waste recycling programmes are listed below:

| S/N |

Programme |

Start Date |

E-waste Collected |

| 1 |

Panasonic’s Heartland E-waste Recycling Programme |

2017 (Phase 3) |

ICT equipment and large household appliances |

| 2 |

StarHub RENEW |

2012 |

ICT Equipment |

| 3 |

SingTel x SingPost ReCYCLE |

2017 |

ICT Equipment |

| 4 |

M1 Drop-off Campaign |

2017 |

ICT Equipment |

| 5 |

Punggol Eco-Drive |

2017 |

ICT Equipment |

| 6 |

City Square Mall E-waste Recycling Programme |

2014 |

ICT Equipment and small appliances |

| 7 |

Project Homecoming |

2011 |

Ink and Toner Cartridges |

| 8 |

IKEA’s Light Bulb Recycling Programme |

2013 |

Light bulbs and fluorescent tubes |

[2] The estimated 60,000 tonnes of e-waste generated in Singapore was derived by surveying sales data of common electrical and electronic products in Singapore.